ESSAY

Inquiring Qyality And Attitude of The Library of Art

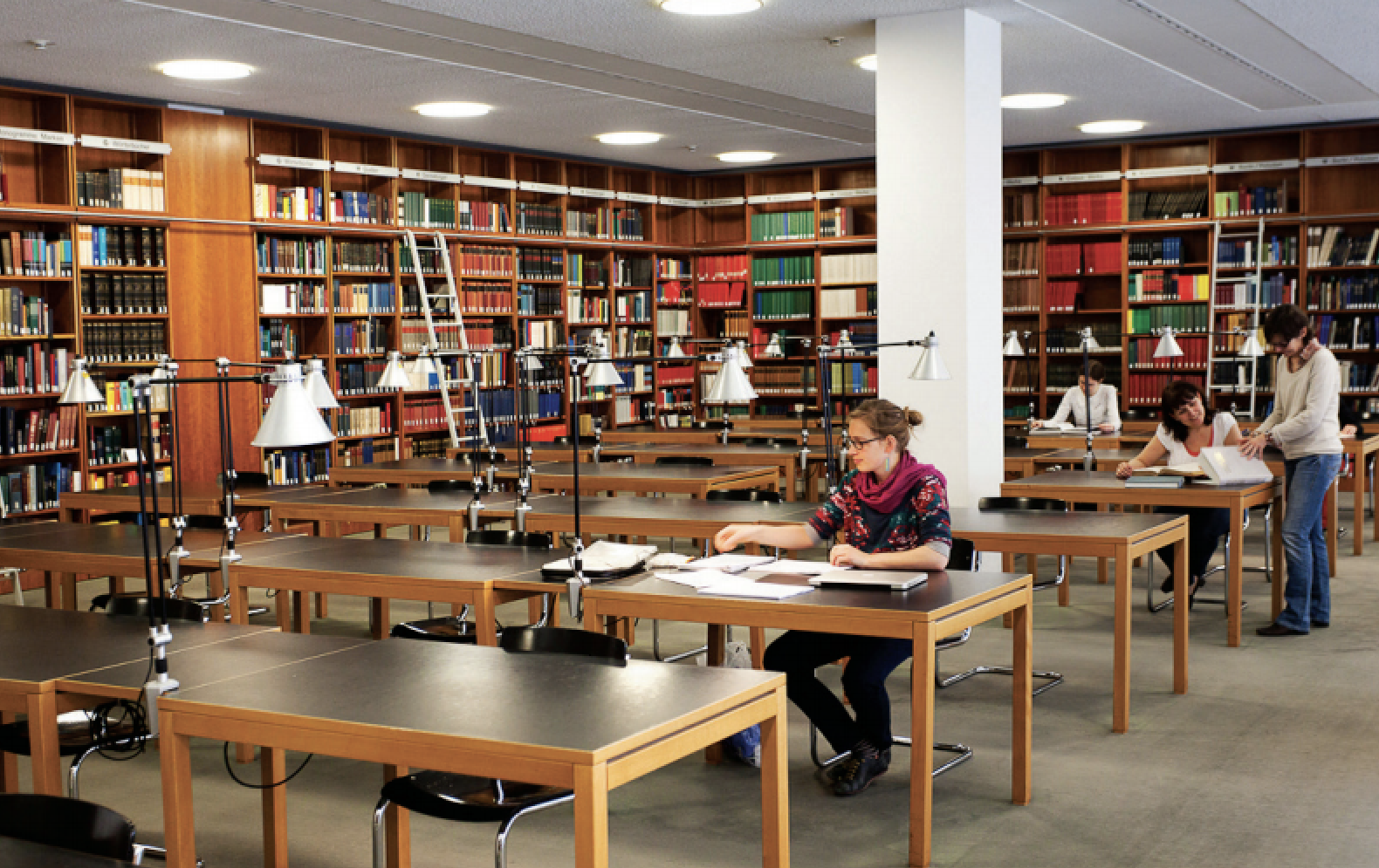

Kunstbibliothek in Berlin marks its 150th year in 2018. It was not easy to comprehend the

significance

of history accumulated over 150 years, which is an impressive lifespan for an arts

and cultural organisation. At the same time, I was curious as to what art libraries do and

how this one had survived for such a long period of time. The Kunstbibliothek is a

highly selective

library that only allows people to inspect their collections after submitting

online applications, but on the other hand it is always packed with visitors there to

experience exhibitions and educational programmes. After reading a news article about

initiatives to establish museum libraries in Korea I decided to look into Berlin’s art library in

more depth. Would it be possible to learn lessons from Europe where some art libraries

have already been operating for more than a century? Both excitement and concern rose

inside me. I kept glancing at my watch while waiting for an interview.

Art libraries in Europe have been created in line with the trajectory of political and societal shifts and the cultural history of each country. The style of operation and character of the organisations is closely aligned with the historical circumstances of the period in which the libraries were established. The history of the United Kingdom’s National Art Library dates back to the Great Exhibition in 1851. The success of the Great Exhibition in The Crystal Palace meant Henry Cole, one of its key organisers, was commissioned to lead other crucial projects for the development of industrial design in the country. It was Cole’s idea to change the name of the School of Design’s library to the National Art Library. By doing so he would like to change it to a national library that collects arts books from the UK and abroad. Later the National Art Library was moved to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1884 and started to collect not only paintings and drawings but also books about architecture, porcelain, glass, textiles and accessories. It also began acquiring livres d’artistes from the start of the 20th Century.1

Art libraries in Europe have been created in line with the trajectory of political and societal shifts and the cultural history of each country. The style of operation and character of the organisations is closely aligned with the historical circumstances of the period in which the libraries were established. The history of the United Kingdom’s National Art Library dates back to the Great Exhibition in 1851. The success of the Great Exhibition in The Crystal Palace meant Henry Cole, one of its key organisers, was commissioned to lead other crucial projects for the development of industrial design in the country. It was Cole’s idea to change the name of the School of Design’s library to the National Art Library. By doing so he would like to change it to a national library that collects arts books from the UK and abroad. Later the National Art Library was moved to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1884 and started to collect not only paintings and drawings but also books about architecture, porcelain, glass, textiles and accessories. It also began acquiring livres d’artistes from the start of the 20th Century.1

Bibliotheque de I’INHA - Salle labrouste ⓒINHA Photo: Laszlo Hovath

Bibliotheque de I’INHA - Salle labrouste ⓒINHA Photo: Laszlo Hovath Kunstbibliothek in Berlin was established

around the same time as the UK’s National Art Library. The discussion around its creation

first began after it was decided to open the royal museum and library to the public as part

of Friedrich Wilhelms Ⅲ’s birthday celebrations in 1830. The organisers devised a 30-year

plan to rearrange museum collections – that used to be arranged in Kunstkammer style –

more systematically and to build a library for public to read books about art and appreciate

books as an artwork.2 Launched in 1868, the library was operated in association with

Germany Arts Industry Museum (current Kunstgewebemuseum) and University of the Arts

(current Universität der Künste Berlin, UdK). The name and affiliated organisations have

changed a few times but its role and functions have remained the same.

Waldemar Tizenthaler, Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin, Ausstellungsraum der Bibliothek, 1906 ⓒKunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Waldemar Tizenthaler, Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin, Ausstellungsraum der Bibliothek, 1906 ⓒKunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin ⓒKunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

ⓒKunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu BerlinIn an interview with Dr. Joachim Brand, Kommissarischer Direktor of the Kunstbibliothek he

expressed his pride about working for a library with such a long history. According to him,

the library has two big categories: general documents or books that include mainly academic documents and exhibition catalogues; and then five collections consisting of approximately 900,000 items. The collections are classified into photography, Buchkunst, graphic design,

architecture, and fashion. There are departments and experts for each category and the

structure of the building and its systems are adapted to each department’s specific needs.

The museum library is not simply a collection of art-related books as it also carries out the

fundamental roles of an art museum, such as collection, preservation, research, and

exhibition.

The Kunstbibliothek, which has consistently created exhibitions since its opening, presented The ABC of Travel exhibition to mark its 150th anniversary. As the title hints at, the exhibition selects themes that start with letters of the alphabet such as A (Album), B (Bericht), and C (Cartographia) under the umbrella of travel, introducing items from their collections related to each theme. From an album with landscape sketches and maps of popular holiday destinations from the 1860s to a poster from 1900 showing the route from Hamburg to the Americas and illustrations depicting women's travel attire in the early 20th century, the items on display are very diverse. While the library's past exhibitions either focused on a certain artistic medium or an artist, this special exhibition explores the rather abstract subject of 'travel'. Brand said: “Travel is a source of artistic inspiration for artists beyond time or geographical space. We wish to provide an opportunity for audiences to explore the history and collections of the library under the theme.”

He then stressed the importance of museum libraries’ exhibition functions. There are some collections that can only be fully appreciated by the audience as part of an exhibition – not just through a single private viewing. Book art is a prime example. It reflects the aesthetic ideas of an artist in all its elements, including its contents, format, and sequence. Since book art was not a traditional mainstream medium like paintings or sculptures, they were produced mainly as 'expensive limited edition books created by renowned artists’(livres d’artistes) in the late 19th century and distributed through auctions or galleries. They began to be produced at scale in the 20th century, crossing the boundaries of art, literature and design, and were produced in a wider variety of types such as artists' books, magazines, book objects and so on by conceptual artists in the 1960s. It was partly because artists used books to draw art away from the institutional system at the time. However, book art was not recognised as a genre in art galleries and libraries. In one famous episode in 1964 the US Library of Congress refused to register Edward Ruscha's artist book, which was deemed neither a photography book nor a literary book.3

The Kunstbibliothek, which has consistently created exhibitions since its opening, presented The ABC of Travel exhibition to mark its 150th anniversary. As the title hints at, the exhibition selects themes that start with letters of the alphabet such as A (Album), B (Bericht), and C (Cartographia) under the umbrella of travel, introducing items from their collections related to each theme. From an album with landscape sketches and maps of popular holiday destinations from the 1860s to a poster from 1900 showing the route from Hamburg to the Americas and illustrations depicting women's travel attire in the early 20th century, the items on display are very diverse. While the library's past exhibitions either focused on a certain artistic medium or an artist, this special exhibition explores the rather abstract subject of 'travel'. Brand said: “Travel is a source of artistic inspiration for artists beyond time or geographical space. We wish to provide an opportunity for audiences to explore the history and collections of the library under the theme.”

He then stressed the importance of museum libraries’ exhibition functions. There are some collections that can only be fully appreciated by the audience as part of an exhibition – not just through a single private viewing. Book art is a prime example. It reflects the aesthetic ideas of an artist in all its elements, including its contents, format, and sequence. Since book art was not a traditional mainstream medium like paintings or sculptures, they were produced mainly as 'expensive limited edition books created by renowned artists’(livres d’artistes) in the late 19th century and distributed through auctions or galleries. They began to be produced at scale in the 20th century, crossing the boundaries of art, literature and design, and were produced in a wider variety of types such as artists' books, magazines, book objects and so on by conceptual artists in the 1960s. It was partly because artists used books to draw art away from the institutional system at the time. However, book art was not recognised as a genre in art galleries and libraries. In one famous episode in 1964 the US Library of Congress refused to register Edward Ruscha's artist book, which was deemed neither a photography book nor a literary book.3

ⓒBavarian State Library /H.R Schulz

Kunstbibliothek is not the only library which collects book arts. Last year, Munich’s Bayerische Staatsbibliothek also held a large-scale exhibition themed on artists' books (Künstlerbücher). The exhibition, titled Show Case, presented a range of artists' books that the library owned, from an illustration collection of William Blake published in 1795 to the latest art publications made in 2017. It also introduced books by Cha Hak-kyung, Yoon Mi-jin and Kim Soo-ja. The excitement I felt from the exhibition lasted quite a long time. I was very surprised at the library’s active role in exhibition and research, and of course I was thankful for the rare opportunity to see so many artists’ books in one place. The library not only showcased their own collections, but a definition and history of artists' books and their own academic achievements in this genre. Would it be an exaggeration if I say I got the impression that the library was rewriting art history? But then again why should that be so surprising? It was the moment I realised how narrow my definitions of library and museum had been.

In the last bit of our conversation, Brand talked about the hardships that they face as a museum library. Books are being produced faster than ever before and their forms and types are boundless. Therefore, it is natural that they are worried about their physical storage limitations as an art library that deals with art, design, and architecture. And there are more things to consider carefully when classifying books. Although their priority is to make their books easy for visitors to find and to create exhibitions, they have to limit access to old books, rare copies, or delicate papers to preserve them. To counter this problem they are digitising their collections, but there are a lot of issues to overcome, including budget, manpower, time and copyright issues.

These issues are relevant to Korea too. This year local governments in cities including Ulsan, Daegu and Uijeongbu announced plans to build art libraries. The aim is to meet the diverse cultural needs of citizens and to revitalise the local economy, and there will be several tens of millions of dollars to be spent. But if these are the aims, why should art libraries be built? In France, the government's plan to build a museum library was postponed for 30 years through various administrations. The Institute National d'Histoire de I'Art (INHA) was finally established in 2001. Today the organisation is largely responsible for fostering art academia and field experts in close cooperation with Bibliothèque d'art et d'archéologie, Bibliothèque centrale des Musées Nationaux (BCMN), Bibliothèque de l'École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, and Bibliothèque de l'École Nationale des Chartes.

Don't get me wrong: I believe Korea needs an art library. However, we have seen earlier that the purpose and vision of the Kunstbibliothek established when it was created still affects its roles and operation today. So we need to ask ourselves this question now: Why do we need an art library? We must devote time to answering this question. European countries spent years preparing to build a single art library through long and arduous processes, whether due to regime change or in the midst of the drastic changes brought about by modernisation. That's why the Koreans plans, which were presented after just a few expert committees and civic discussions, do not sound very hopeful. The organisations in the plans might turn out to be white elephants that are neither museums nor libraries. The effusive sentences that were written in the plans selling the idea to local people were particularly worrisome.

1. Gernot U. Gabel, Die “National Art Library in London”, Bibliothekdienst 40. Jg, 2006, H.1. p. 9.

2. Die Bibliotheken der Staatlichen Museen zu Belrin-Preußischer Kulturbesity, Dr. Johachim Brand, Fachhochschule Köln, Fachbereich Bibliotheks- und Informationswesen Köln, 2000, p. 8.

3. Ruscha, Ed, Leave Any Information at the Signal: Writings, Interviews, Bits, Pages, eds. Alexandra Schwartz, Ed Ruscha, New York: The MIT Press, 2004, p. 86.